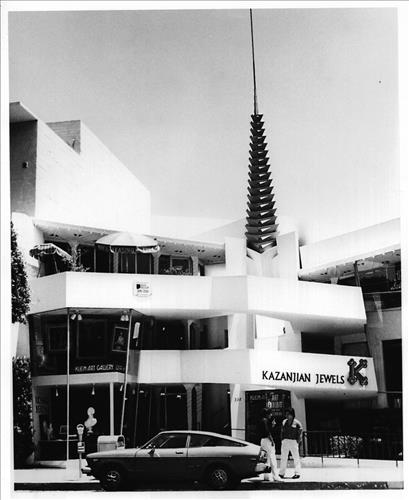

The Anderton Court Shops designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1952 is eligible for the National Register under Criterion C at the local level because it represents the only retail structure designed and built by master architect Frank Lloyd Wright in Southern California, and is also eligible under Criterion C at the national level as one of the very few primarily retail structures ever designed by Wright. The complex retains a high degree of integrity, suffering only minor alterations over the years.

Context

Frank Lloyd Wright maybe the most celebrated and highly recognized American architect. Certainly, he has had a major impact on the face of 20th and 21st century architecture. At least fifteen buildings designed by Wright have been declared National Historic Landmarks, which testifies to the significance of the architect and his legacy.

Throughout his long and productive career, Frank Lloyd Wright designed only eight buildings in the Los Angeles area. A majority of these structures fall into the concrete textile-block construction category of the 1920s, including most notably the Alice Millard House (La Miniatura) in Pasadena (1923) and the Ennis-Brown House in Los Angeles (1924-26). The Anderton Court Shops (1952) is significant because it is the only non-residential building Wright designed in Southern California and is the only primarily retail complex Wright built designed from the ground up. It stands alone in Beverly Hills as a work of this master architect, who described it in a letter to Nina Anderton as "a little gem of an unusual sort." The hexagonal floor plan and ramp, based on a diamond grid pattern, was rhythmic and meant to stimulate the imagination. The geometrical shaping and angular features created an environment that has been described as "[seeming] like part walk-through sculpture and part retail complex." Considered to be "one of his zaniest productions," the court shops express the "try-almost-anything spirit that characterized his prolific final years."

The 1950s were a pivotal period in Wright's career. Up to this point most of his architectural work had been confined to residential commissions. In 1950, while he began to sketch ideas for the Anderton Court Shops, he was also working on forty different designs for residential buildings. By 1957, of the fifty-nine new projects in Wright's studio, only twenty-five were residential. A greater portion of his architectural work now consisted of non-residential buildings, the majority being commercial, civic, cultural, religious, medical, educational or governmental structures.

Wright strongly preferred to express his architectural vision through residential designs, and at least in the earlier periods of his career his designs for non-residential buildings were greatly outnumbered by his residential designs. As he entered the later periods of his career, the number of non-residential commissions he accepted grew, but only three retail buildings designed by Wright are extant: the-Anderton Court Shops, the V.C. Morris Gift Shop in San Francisco (1948), and the Hoffinan Auto Showroom (1954) in Manhattan. Both the V.C. Morris Gift Shop and the Hoffinan Auto Showroom were pre-existing structures remodelled to Wright's designs. In V.C. Morris Gift Shop, the only other retail space he designed in California, he renovated what was once a warehouse into a single open space for the display of fine glass and china. As an example of retail design, the Anderton Court Shops is the only structure Wright designed containing multiple stores within a single complex.

In 1985-86, the Anderton Court Shops was documented by the City of Beverly Hills as being "one of the city's most significant properties...[and] the only work within the city of this master of American architecture."

"Untrue to say that any store I have done or might do either 'upsets' any 'rules' of 'commercial architecture' or sets up new ones of its own. Correct to say, that what unfailingly interests me is the exception, as necessary to prove any rule both useful and useless. In organic architecture every opportunity stands alone."8 Frank Lloyd Wright made this statement to Architectural Forum in 1950 in regard to his design for the V.C. Morris Gift Shop in San Francisco (1948), and he eloquently summed up his architectural philosophy. As elegant and fluid as his design was for the gift shop Wright set off in a different direction when he designed the Anderton Court Shops in Beverly Hills four years later, but held to his theory that "every opportunity stands alone."

Wright's initial design for the structure was intended to highlight its commercial use, but according to his apprentice, the layout of the shops did not necessarily offer any new innovative ideas in retail planning. As the project evolved shops were designed just as spaces to be developed, and "there was no program for specific usage." The three-story court, with its angular ramp leading up and around a hexagonal well of light crowned by a spire fitted with interior lights, "looks to some like a sci-fi tower [and] to others like a single ear of wheat." The towering spire foreshadows that of the Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael, California (1957), which is one of Wright's later civic works. The spire was meant to draw attention to the complex on a street otherwise lined with flat roofed structures. Large display windows make up much of the front elevation, and the central display window at the base of the spire was "especially placed for one of [Eric Bass's] figures in costume."

Making up a large portion of the southern facade is a cantilevered window, a common feature of Wright's designs. The use of the cantilever among his residential designs "freed homes from boxiness [and] opened their spaces to the surrounding environment." The inverted-V shape of the facade, which expands the street into the court, was Wright's attempt at adding a "third (depth) dimension to the dreary repetition of the box-fronts characterizing the street." Wright's intention may also have been ‘to overcome the limited street exposure of an expensive site" by "[continuing] the street into the building, as a linear spiral ramp, to provide each shop with window frontage." It also provided an area to step away from the main sidewalk for calmer browsing. The large circular windows lining the second and third floor hallways offered alluring glimpses into the shops and created a look that was "somewhat nautical and streamline moderne."

The structure is constructed of reinforced concrete, which was then covered in plaster. Wright's use of concrete dates back to his design for the Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois (1906), which was one of the first non- industrial building to be constructed using poured concrete. Up to this point concrete was almost exclusively used for fireproofing, but it was a bold move to use this inexpensive material to create an artful form. By the 1950s, an improved technique of applying a concrete mixture, or gunite, over steel reinforcements was being used with more frequency. In the early 1900s the cement gun was developed as a device to spray a strong thin layer of a mixture of sand and cement onto wire or steel frames. This dry process method was commercialized for the construction industry and was used exclusively until the wet process was developed in the 1950s, which allowed for more accuracy and was more cost effective. The wet process of gunite application was a clean procedure creating results that didn't sag and was best exemplified in the base of the spire, which was sculpted after the gunite was applied. Because this was the bulk of the work, and was an easy procedure to perform, no general contractor was needed. In order to increase the building's fire resistance, Wright applied a technique he had used earlier in the Hillside Home School at Taliesin for the roof construction. "Concrete was poured over mesh-covered wood beams spaced four feet apart, and plaster was used for the interior finish." Wood beams on the ceilings of the shops were to remain natural in color, but could, according to Wright, also be painted Cherokee red or veneered with thin plaster. In the original design, a fireplace was placed into each shop and was meant to create an intimate atmosphere.

The spiral ramp was a prominent feature in the interior of the V.C. Morris Gift Shop and was used as a means of displaying items in the circular openings along an upward path. It is a completely internalized retail structure bound by an imposing exterior wall of raked brick and a monumental Roman arched entry reminiscent of Wright's mentor Louis Sullivan. In stark comparison, the Anderton Court Shops complex is open to the elements, which was eminently suitable for the temperate Southern California climate. The centrally placed outdoor ramp was a means of getting from one shop to another. But as different as these two structures are architecturally, they both achieve the same results. Each structure is designed specifically to entice pedestrians to enter into a shopping experience, and both have become successful works of architecture. Architect Matt Taylor worked across the street from the V.C. Morris Gift Shop in the 1950s and recalled how people responded to the building, "I realized that the building defined a PROCESS. In this case it was a gentle, but powerful, process of introducing and selling merchandise. V.C. Morris was a work of art and earned its living supporting a commercial enterprise - without compromise to either assignment. Here was an example of embedding a pragmatic process in art." Similarly, the inverted "V" entry and the ramp system employed in the Anderton Court Shops "is very inviting and pushes you to continue looking," as one shopper quickly noticed when asked for an opinion about the unique structure.

Links have been made between Wright's Guggenheim Museum and the Anderton Court Shops specifically because of the use of the ramp, but according R. Joseph "Joe" Fabris - an apprentice of Wright's who supervised the shops' construction - this association is most likely a later invention of architecture critics. Wright was clearly experimenting with ramp designs during this period in other designs of this period, particularly the Guggenheim, the V.C. Morris Gift Shop, and the Hoffinan Auto Showroom.